This is a response to the ridiculous chess180 post on the usually excellent Streatham & Brixton Chess Blog.

By most measures, 180 ECF is a pretty decent level of chess - not outstanding, but not bad.

In the January 2014 ECF grading list, there were around 800 UK players (including Jonathan Bryant) graded 180 or above, and over 9,000 (including me) graded 179 and below.

|

| 180 - it's pretty good |

Unless you're some sort of child prodigy, getting to 180 ECF is hard. But staying at 180 is harder - anyone can improve or get worse at chess, but staying where you are takes some effort.

From a level where there's so much improving to do, for someone who takes the game seriously enough to play most weeks during the season, and writes a blog dissecting his games and those of others, improvement should be almost guaranteed.

Jonathan claims to be "more 180" than me - but let's take a look at the real facts about who of me and Jonathan is the most dedicated 180-strength player.

Who's more 180?

I re-started playing chess in 2011, after a few years off. My grade in the July 2011 ECF list? Interesting you should ask - it was exactly 180. Compare this to Jonathan Bryant's grade of only 172.

In fact, if you look at all six grading lists from 2011 to 2014, my grade was within 5 points of 180 in every list - it's only in the last list that Mr Bryant has even got close.

|

| Who's more 180? |

So clearly I'm a more dedicated 180 than Jonathan - I'd suggest that such an improvement in grade over the last couple of years is pretty amateurish for someone who claims to be the "most 180 of them all".

If you want to stay 180 Jonathan (and I'm assuming you do), I'd hold off on the rook endings and play some more dodgy exchange sacs.

The most 180 of all?

More dedicated than Jonathan I may be, but am I the most 180 of all? Absolutely not. Looking at the ECF gradings, there is a man who has been exactly 180 on all of the last 4 lists. Step forward Nick Keene of Wimbledon, the most 180 of all.

Now that's dedication to a grade...

Following a long lay-off from blogging for various reasons (but not from chess - I'm quite a few games behind, including some instructive losses) I've finally found myself with

- a bit of time to write the blog

- a game that (in my opinion) is interesting enough to discuss here

So here it is! There's no particular lesson but I was quite happy with my judgement of the position throughout (though I didn't quite manage to calculate all the complexities).

White - Matt Fletcher (179)

Black - Charlie Allum (144)

13 March 2014

30 moves in 75 minutes, plus 15 minutes for the rest of the game.

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Nd7

The Caro-Kann defence, Modern variation. I almost played 5. Qe2 here, purely because of the line 5... Ngf6?? Nd6 checkmate.

But I assumed my opponent, an experienced player, would know to play a move like 5... e6 instead! So I played something else.

5. Nf3 Ngf6 6. Ng3 g6

This is playable, but quite a rare move - normally in the Caro-Kann, Black wants to play e6 and later c5, and this makes it much harder to follow this plan. As a result, 6...e6 is much more common here. After ...g6 Black needs to be a bit careful not to get to a position that's like a Sicilian but where he's taken two moves instead of one to play c5.

7. Bc4 Bg7 8. Qe2 e6?!

Black now needs to be very careful on the black squares, particularly d6 and f6 (and maybe h6) - if the black-squared bishop is taken, there will be real problems. Also, playing e6 makes life slightly difficult for his white-squared bishop.

9. h4 h5 10. Bg5 0-0 11. 0-0-0

Anticipating attacks on both sides, and hoping that my lead in development will tell.

11... b5 12. Bd3 Qb6

All my pieces are now developed and well-placed, and I felt there should be a breakthrough on the cards with a few more preparatory moves. On the flipside Black's pieces (other than the Bishop on c8) aren't too bad and if I'm too slow then Black can build up on the Queenside fairly quickly.

Here I thought for a long time (almost 20 minutes) to work out how best to press my advantage. I came up with:

13. Ne5

I think this is a pretty decent move - there are some options for Black but the obvious choice is to go down the lines below. Interestingly, my computer isn't at all keen on this move - but it still suggests taking the Knight which seems to lead by force to some lines that give White a pretty big advantage.

13... Nxe5 14. dxe5 Nd5

I'd expected 14... Ng4 when I'd analysed 15. f4! Nf2 16. Nxh5! Nxh1 17. Rxh1 gxh5 18. Qxh5 or 16... Nxd3+ 17. cxd3 gxh5 18. Rg3 (actually 18. Bf6 is even better!)

Or 14... Nd7 15. f4 Nc5 16. Ne4 Nxd3+ 17. Rxd3 which is similar.

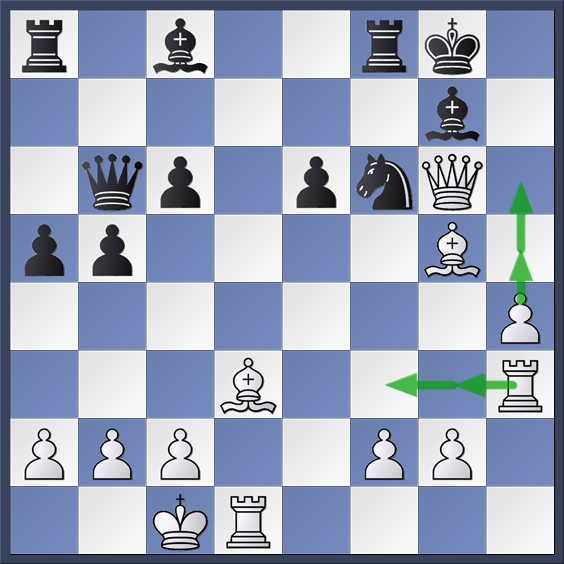

After Black's 14th move, I had a close look again at 15. Nxh5 but couldn't find a clear win. I then noted that there was nothing Black could do to defend h5, and decided that if I was going to play Nxh5, I'd want to have the Rook on h3 instead of h1. So I looked at options for Black after 15. Rh3.

15 ... Nb4 looks like it could be interesting but I managed to calculate that 16. Nxh5! still works - 16... Nxa2+ gets nowhere but 16... Nxd3+ 17. Rdxd3 gxh5 18. Rhg3 is going to win pretty quickly.

[Looking at the game afterwards, it turns out that the sacrifice is sound on move 15 (the lines are very similar to those below).]

15. Rh3!? a5 This potentially gives Black the option of defending across the rank with Ra7 in some lines. Again I spent some more time (another 8 minutes) to see if I could calculate a clear win after Nxh5 - I failed but I got far enough to be happy that my attack should be too strong.

16. Nxh5!

My calculations ran 16... gxh5 17. Qxh5 f5 18. exf6 e.p. Nxf6 19. Qg6! where the Rook can switch to f3 or g3, or the h-pawn runs.

Amusingly (though I didn't spot this till afterwards), after 19... Qxf2?? 20. Be3! just traps the Queen!

I also thought about 17. Bf6!, because 17...Bxf6 blocks the f-pawn's advance so that 18. Qxh5 is hugely strong as it can't be met by 18... f5. This is a motif worth remembering when attacking h7 like this - if f5 is a resource, can it be blocked?

Instead 17... Nxf6 18. gxf6 looked (and is) equally hopeless for Black. The move that worried me was 17... Nf4 forking Queen and Rook - in the light of day, this isn't a threat because of 18. Qf3! when Black has no time to take the Rook as 19. Qg3! is coming.

After the game, I discussed this position with some chess-playing friends on Twitter and came up with some more interesting analysis.

Jonathan Bryant suggested the inventive and excellent 17. Bh7+! Kxh7. He initially wanted to follow up by taking off the Knight on d5 with the Rook which unfortunately just about fails because Black can take the f-pawn with his Queen at a vital moment. But 18. Qxh5+ Kg8 19. Bh6! is quickly decisive.

Pablo Byrne suggested that Black might want to try getting counterplay with 16...a4 instead of 16... gxh5, ignoring the Kingside attack and going for something on the Queenside. A sample line is 17. a3 b4 (really going for it) 18. Nxg7 bxa3 (still ignoring the Kingside) 19. bxa3 Nc3 (and still) 20. Qf3 Qb1+ 21. Kd2 Qxd1+ 22. Qxd1 Nxd1 23. Kxd1 Kxg7

Unfortunately for Black, after heroically ignoring the Kingside for so many moves, even an extra exchange isn't going to save him after 24. h5! which just wins in all lines. For example 24... gxh5 25. Bf6+ Kh6 26. g4 Rg8 27. Rxh5#. Pretty!

In the game, my opponent just thought he was getting mated (as you can see above, he probably is doomed, but perhaps not as quickly as he'd anticipated) so he played the horrendous 16... f5?? which just gives me everything I'd have got from the en-passant line above, but with an extra piece. The game ended:

17. exf6 e.p. Nxf6 18. Bxg6 Nh7? 19. Bxh7+ Kxh7 20. Nxg7 Kxg7 21. Qe5+ Kg8 22. Rg3 Qb7 23. Be7+ Kf7 24. Qg7+ Ke8 25. Rd8#

Quite a comprehensive checkmate - Black's c8 Bishop and a8 Rook never made a move! I was pretty happy with the standard of my calculation in this game (if not the speed) and that having calculated to what seemed to be a decisive position I managed to make the pragmatic decision to make the sacrifice 16. Nxh5!